On Wednesday, Sept. 18, the Federal Reserve reduced its benchmark interest rate for the first time since March 2020, during some of the worst of the COVID pandemic. The 50-basis-point cut, which came months later than most anticipated at the start of 2024, is meant to provide a jolt to a slowing economy and is widely expected to be one of the final stages in the Fed’s attempted economic “soft landing.”

Also on Wednesday, Sept. 18, I was smack-dab in the middle of a weeklong vacation in Portugal with my family.

And as much as I like y’all, I like ancient churches, fresh seafood, and port wine more, so we had to kick the Fed analysis can down the road by a week.

But, like I said, I do like y’all, so as a token of apology, I’ll spend the next two weeks providing you with two separate deep dives on how the Fed’s rate cuts will affect you.

- Part I (this week): How rate cuts impact your wallet

- Part II (next week): How rate cuts impact your portfolio

Vamos começar!

The Tea: The Federal Reserve, as mentioned above, just cut its benchmark interest rate for the first time in years.

This federal funds rate is the rate at which banks lend money to (and borrow money from) one another. More importantly to you and I, it’s a critical benchmark for all manner of other interest rates that affects us in oh so many ways:

- It determines the rates on lending products such as mortgages, car loans, and student loans.

- It impacts the return on fixed-income investments such as bonds and annuities, as well as the rates you receive on savings products like high-yield savings accounts and certificates of deposit (CD).

- It also affects corporate borrowing rates, which combined with the other effects outlined above, can have a significant impact on the direction of the stock market.

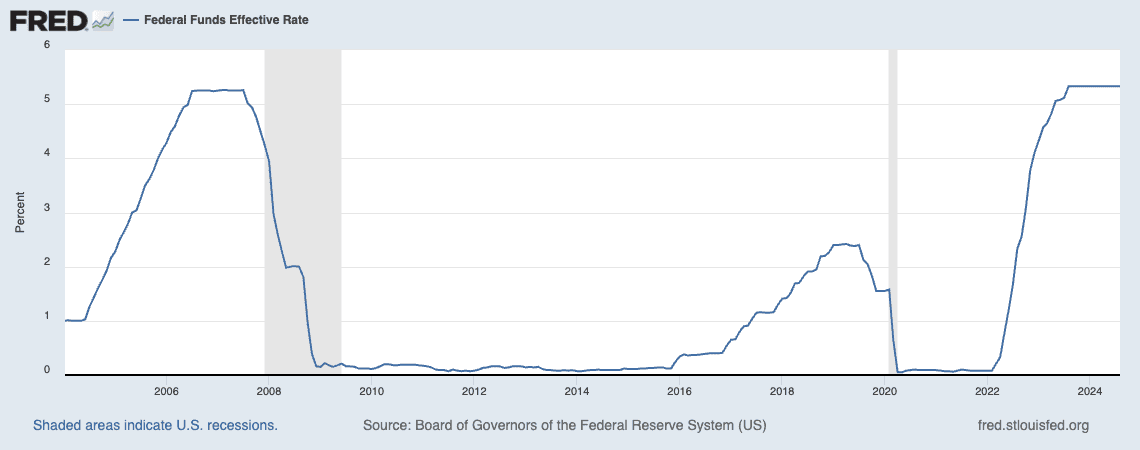

It’s also a tool. The Federal Reserve can use its benchmark rate to correct the economy if it veers too hard in one direction or the other. The Fed will raise rates (much like it did in 2022 and 2023) to cool an overheated economy and tamp down inflation, but it will lower rates (as it has started right now) to combat a slowing or even recessionary economy and fend off high unemployment.

WealthUp Tip: Despite the name, a savings account isn’t always the best place to save money.

And as you can see, the Fed’s September cut (not yet reflected in the St. Louis Federal Reserve data shown below) isn’t just the first cut in some time—it also takes us down from high-water levels we hadn’t even neared in almost two decades.

This move (and what the Fed does going forward, which we’ll also talk about next week) is expected to have a massive impact on just about anything and everything financial—the economy, the labor market, the stock market, the bond market.

And that impact won’t just be felt at some high level.

It will impact you—how you spend, how you save, and how you borrow.

The Take: Today, I’m going to limit the conversation to what this means for your personal finances. While your investment portfolio is an important part of your overall financial picture, there’s a big difference between the money you can touch today and the money you probably don’t intend to touch for a few decades.

And how it impacts you largely depends on your personal financial situation and the types of financial products you need and/or have.

Earlier this week, I interviewed Jeff Weniger, Head of Equity Strategy at WisdomTree, about the investment side of the interest rate discussion. But he also provided an example of how everyone’s wallets won’t necessarily be impacted in the same way:

“So there’s a type of person that’s getting hurt here,” he says. “Maybe they’re independently wealthy. They’ve got a Marcus [high-yield savings] account throwing off 4.5%, or a Discover account throwing off 5%, and they have $100,000 in there. This is the type of person who’s going to be adversely hurt. They’re no longer getting 5%; they’re going to be getting 3% to 4%.

“That’s a huge difference from a person who’s getting a few percentage points less to pay off their credit card, or a person who is in the market for a used car.”

That brings us to the two most direct ways changes in the federal funds rate will impact our personal finances: rates on debt products, and rates on savings products.

Interest Rates and Your Debt

As I mentioned above, the federal funds rate directly impacts banks by determining the interest on what they loan one another.

But that ultimately filters down to us through the “prime rate.”

The prime rate, which affects consumer debt products like loans and credit cards, is the rate banks will charge their highest-quality (read: highest-credit-quality) customers. And it’s indexed to the fed funds rate. Typically, the prime rate will simply be the Fed’s benchmark (currently 4.75%-5.00%) plus 3 percentage points (7.75%-8.00%), though this can vary. (And as you might have guessed, if you have less-than-ideal credit, you’ll pay more than the prime rate.)

Still, a lower federal funds rate means a lower prime rate, and a lower prime rate means lower interest rates charged on a wide variety of debt products.

Net-net, that’s good news for the average American.

“The Fed’s … interest-rate cut, coupled with moderating inflation, should help ease the financial strain on lower- and middle-income consumers,” says Joe Gaffoglio, President and CEO at Mutual Of America Capital Management.

Just keep in mind that some of these debt products, such as mortgages and auto loans, are typically fixed-rate in nature. In other words, new mortgages will reflect these lower rates. But if you have an existing mortgage, a decline in the prime rate won’t automatically reduce your mortgage rate—you would have to refinance to see any benefit. Even then, refinancing would only make sense if you could do so at a rate lower than what you originally signed up for on your mortgage.

You will, however, see an automatic change if you have a variable-rate product, such as a credit card or a home equity line of credit (HELOC).

Credit cards, for instance, have variable annual percentage rates (APRs), which are also tied to prime rates (though they’ll be much higher than the prime rate no matter how pristine your credit is).

So, when prime rates change, your APR will likely change, too.

But major credit bureau Experian notes this change isn’t immediate: “Timing varies: Some rates change within a month, while others may take a bit longer to adjust,” it says.

In summary, lower fed funds rates …

- Are great if you want to take on a new mortgage, auto loan, student loan, or personal loan

- Are great if you want to take out, or currently have, a home equity line of credit

- Are great If you carry any debt on a credit card

- Can be great if you want to refinance an existing mortgage or other fixed-rate loan (but the rate typically needs to be below what you own right now).

Interest Rates and Your Savings

On the flip side, you typically won’t love what a lower fed funds rate means for your savings options.

Here’s a helpful way of thinking about this: When you open a savings account, you’re effectively lending the bank money, which it will pay back with interest. So, if you’re suddenly paying less interest when you borrow from the bank … well, the bank is suddenly going to pay less interest when they borrow from you.

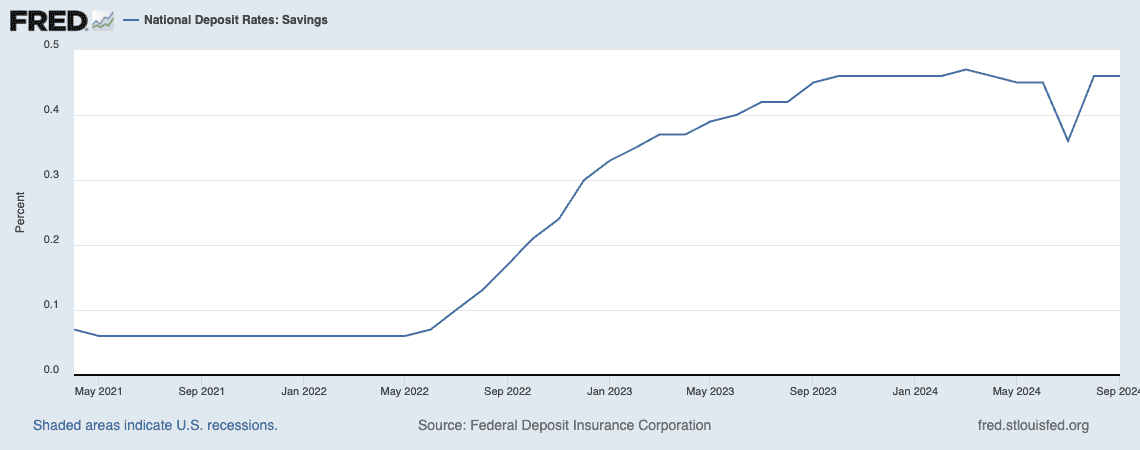

This won’t matter much if you have a traditional savings account, as these usually already pay a nominal annual percentage yield (APY). Still, even in the St. Louis Fed’s limited data set (going back to just 2021), you can see how much of an impact the federal funds rate can have on savings rates.

The impact can be even greater on higher-income products, such as a high-yield savings account (HYSA) or certificate of deposit (CD).

Also, the same logic applies here as to debt products. If you have a product that’s fixed, like a CD, your rate will stay the same—in the case of a CD, you’ll receive whatever rate you signed up for at the beginning of your term. But HYSAs and money market accounts (MMAs) are variable in nature, so you could immediately start seeing reductions in your APY.

While this does bleed into the realm of investments, all of the above applies to bonds and other fixed-income investments, such as Treasuries or corporate debt.

When you buy a Treasury bond, you’re lending money to the U.S. Treasury, which will pay you back with interest. Thus, as the federal funds rate goes down, you’ll generally see a decline in rates on new Treasuries (and other new bonds, for that matter).

WealthUp Tip: Being frugal can be a good way to save money … but in some cases, you’ll doom yourself to paying more over time.

But that’s not a total loss—when rates go lower, that also makes the rates on existing bonds look more attractive by comparison, which drives up the value of those existing bonds. Thus, bond investors can both suffer and benefit from reduced interest rates.

In summary, lower fed funds rates …

- Are harmful if you want to open an HYSA, MMA, CD, or other savings product linked to interest rates.

- Are harmful if you currently have money parked in a variable-rate savings product like an HYSA or MMA.

- Aren’t harmful if you currently have money in a fixed-rate savings product like a CD.

- Are harmful if you want to buy new bonds.

- Can be either harmful or beneficial if you currently own bonds.

Indirect Impacts

The Federal Reserve has a “dual mandate.” In the words of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, that’s “pursuing the economic goals of maximum employment and price stability.”

Put even more simply: The Fed’s primary goals are to keep inflation low and employment high.

Again, this goes back to remembering that the federal funds rate is a tool. By raising its benchmark interest rate, the Fed can make purchases such as homes and autos artificially more expensive, and also make corporate borrowing more pricey, which in turn can slow economic growth (i.e., reduce inflation) … though it does so at risk of also harming employment levels. Conversely, by lowering its benchmark rate, the Fed can make those big-ticket purchases less expensive, stimulating economic activity, and also make corporate borrowing less expensive, which can stimulate hiring … though it does so at the risk of increasing inflation.

Right now, the prevailing opinion is that the Federal Reserve reduced its benchmark rate with an eye on keeping employment at healthy levels.

WealthUp Tip: Does your job not offer a 401(k)? Here are the best alternatives.

“The key message from the Summary of Economic Projections is that the Fed is more worried about the labor market and less concerned about inflation at this point,” says Candice Bangsund, Vice President and Portfolio Manager, Global Asset Allocation and Private Markets Solutions, at global asset manager Fiera Capital. “The median respondent expects the unemployment rate to sit at 4.4% by year-end, up from the latest reading of 4.2% and core inflation to moderate to 2.6%. This highlights the increasingly balanced approach vis-à-vis the dual mandate, which the Fed will need to take into consideration moving forward.”

Or if you prefer brevity, Carson Group’s Global Macro Strategist, Sonu Varghese, nails it in a dozen words:

“The message here is that the Fed’s got the labor market’s back.”

Importantly, though, the heading here is “indirect impacts.” For good reason. The Fed is hardly the only factor in both employment and inflation—and controlling interest rates is only so effective.

For instance, if the Fed lowers its benchmark rate, that will certainly help to make home and auto purchases less expensive … but it won’t necessarily do much to make your grocery bill any cheaper.

—

Thank you again for taking the time out of your weekend to read our thoughts!

Editor’s Note: Kyle here! I was the one on vacation, so I’m to blame for the delayed Fed discussion. Also, if you’ve never been, take a trip to Porto. Fresh air, great seafood, lovely wine (and not just port!), rich culture, and low prices … at least for now.

Riley & Kyle

Like what you’re reading but not yet a subscriber? Get our weekly financial insights and updates delivered to your inbox every Saturday morning by signing up for The Weekend Tea today! You can also follow Young and the Invested / WealthUp on Flipboard for more great advice and insights.