Did you sell property, such as, stocks, bonds, cryptocurrency, real estate, or precious metals, last year? If so, don’t forget that you might owe capital gains tax when you file your 2024 tax return next year (returns for the 2024 tax year are due April 15, 2025, for most people and extensions grant you up to October 15, 2025).

But don’t be too upset. While nobody likes to pay taxes, at least you’ll pay a lower tax rate on your profits when compared to income taxes on wages, interest, withdrawals from tax-deferred retirement accounts, and other forms of “ordinary” income.

At the end of the day, minimizing the tax hit when you sell assets requires a solid understanding of how the capital gains tax works. You need to be familiar with both the tax benefits and traps—and I can help you with that. The following discussion will cover the capital gains tax basics, point out the landmines to avoid, touch on a special surtax that might apply, and even provide some tips on how to cut your capital gains tax bill to the bone.

Table of Contents

What Is the Capital Gains Tax?

As the name implies, the capital gains tax is imposed on any gain (i.e., profit) from the sale of capital assets. The tax is typically paid when you file your federal income tax return for the year the asset is sold. The capital gains tax rate that applies to your profits depends on whether your gains are long-term capital gains or short-term capital gains.

In addition, you only have to pay capital gains tax if your gain is “realized.” A gain is not realized until you actually receive the profit following the sale or other disposition of a capital asset. As a result, you won’t incur capital gains taxes on stocks or other property you own that increases in value until you sell it, since the increase in value is an “unrealized” gain until that point.

What Are Capital Assets?

The capital gains tax only applies when you sell or otherwise dispose of capital assets. With a few exceptions, capital assets include all your investment property, such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, cryptocurrency, precious metals, and the like. However, personal items—such as your car, home, furniture, stamp collections, jewelry, and so on—are also capital assets.

If you sell a small business, all the business’s assets are generally treated as being sold separately. As a result, some of the business’s property will likely be considered capital assets, while other items will not.

Long-Term Capital Gains vs. Short-Term Capital Gains

The distinction between long-term capital gains and short-term capital gains is very important, because the two are taxed at different rates. The rules for offsetting capital gains with capital losses also depend on whether you have long-term or short-term gains and losses. (The capital gains tax rates and capital loss rules are discussed later.)

Generally, if you hold an asset for more than one year, any profits from the sale of the asset are considered long-term gains. Short-term capital gain results from the sale of assets held for one year or less.

Related: How to Give Stocks as a Gift in a Tax-Efficient Way

To determine how long you held an asset, start counting on the day after the day you acquired the property, and then count the day you disposed of the property as part of your holding period. For example, if you bought stock on Nov. 15, 2023, the clock started running on Nov. 16, 2023. If you sold the stock for a profit on Nov. 16, 2024, you didn’t hold it for more than one year, so you have short-term capital gain. However, if you sold the stock on Nov. 17, 2024, you have a long-term capital gain because you held it for more than a year.

Related: 10 “Most Serious” IRS Problems Taxpayers Face

Calculating Taxable Capital Gain

The profit subject to the capital gains tax is generally equal to the amount you receive from the sale of an asset minus your “adjusted basis” in the property. (You have a capital loss if you sell a capital asset for less than your adjusted basis.) So, the higher your adjusted basis, the lower your capital gains tax.

Basically, your adjusted basis in an asset is the amount you have invested in the property. Start with your cost basis, which in most cases is your purchase price, plus sales tax, broker commissions, legal fees, and various other expenses related to your purchase. That amount is then increased by the cost of items that add value to the property, such as improvements to real estate. It’s then decreased by certain property-related benefits you previously received, such as stock splits or tax deductions for depreciation.

Young and the Invested Tip: Tax software like TurboTax or H&R Block will include a capital gains tax calculator and figure the total capital gains tax due. However, you might have to upgrade to a more expensive version if you have capital gains or losses. If you’re looking for the right tax software for you, check out our review of the best tax software products available.

Related: What Tax Bracket Are You In?

Capital Gains Tax Example

Cheri bought 100 shares of stock for $1,500. That’s an original cost basis of $15 per share. She also paid a $20 brokerage fee for the transaction. After a stock split, Cheri owns 200 shares of the stock. Although her overall basis in the stock has not changed, her adjusted cost basis is now $7.50 per share. Two years after the stock split, Cheri sold 100 shares for $2,000 ($20 per share). Her adjusted basis for the 100 shares she sold is $760 [$750 (100 x $7.50 per share) + $10 (50% of brokerage fee)]. As a result, she has $1,240 of long-term capital gain [$2,000 sales price – $760 adjusted basis = $1,240 capital gain].

Like Young and the Invested’s content? Be sure to follow us.

And If You Didn’t Buy the Capital Asset? Alternatives to Cost Basis

What if you didn’t buy an asset? How do you establish a cost basis if you received property as a gift, inherited it, or obtained it in some other way that isn’t a traditional purchase? In many cases, the property’s fair market value (FMV) or adjusted basis is used instead of cost basis.

Here are a few examples of alternative basis starting points that you might encounter:

— The basis of inherited property is generally the property’s FMV at the date of the previous owner’s death. This is commonly referred to as “stepped-up basis.” With a stepped-up basis, if you immediately sell inherited property for FMV, you won’t pay capital gains tax since the sale price will equal your basis.

— If you receive property as a gift, your initial basis can either be the donor’s adjusted basis or the property’s FMV when you received the gift, depending on the donor’s adjusted basis just before the property was given to you, its FMV at the time of the gift, and whether you have a gain or a loss when you dispose of the property. Your basis can also be increased by any gift tax paid.

— If you replace destroyed property with similar property (e.g., property lost in a natural disaster), the old property’s basis generally becomes the replacement property’s basis. The basis must then be decreased by any loss you recognize and any money you receive that you don’t spend on similar property. It is increased by any gain you recognize and any cost of acquiring the replacement property.

— For property received in exchange for services, the property’s FMV is your basis (and must be reported as taxable income). If a price is agreed upon before services are provided, that price will generally be accepted as the property’s FMV unless there’s evidence to the contrary.

Related: Best TurboTax Alternatives [Tax Software Like TurboTax]

One Capital Gains Tax Exclusion To Know: Home Sale Exclusion

There’s an important capital gains tax exclusion you might qualify for if you sell your home. The exclusion is worth up to $250,000 ($500,000 if married filing jointly), but the real estate sold must be your primary residence (i.e., main home).

To claim this exclusion, you generally must own your home and use it as your primary residence for at least two of the five years immediately preceding the sale of the home. You can only claim the exclusion once during a two-year period, too. The exemption isn’t available if you acquired your home through a like-kind exchange within five years or you’re subject to the expatriation tax (e.g., you’re a U.S. citizen who has renounced your citizenship or a long-term resident who has ended your residency).

Related: Tax Preparation Checklist [Get Your Tax Documents In Order]

The two years of residence can be at any time during the five-year period, and it can be broken up into separate chunks of time. You just need a total of 24 months (730 days) of residence during the five-year period.

If you’re married, only one spouse has to own the home for the two-year period. However, each spouse must use the home as their primary residence for two years.

If you don’t satisfy the ownership and residency requirements, you might still qualify for a partial capital gains tax exclusion if you sell your home because of a change in your job location, health issue, or unforeseeable event.

There are also some exceptions to the eligibility requirements for separated or divorced spouses, widow(er)s, military personnel, owners of destroyed or condemned homes, and others. Check IRS Publication 523 for details.

Related: Child Tax Credit FAQs [What Every Parent Needs to Know]

Capital Losses

What if you sell property for a loss? While you generally don’t want to see an investment lose value, capital losses can be beneficial from a tax perspective, since they can be used to reduce the amount of taxable capital gain. Plus, if you have a net capital loss after offsetting gains with losses, you can use a certain amount of the net loss to reduce your “ordinary” taxable income.

As with capital gains, capital losses are classified as either short-term or long-term losses. Again, if you sell an asset held for one year or less, any resulting loss is a short-term loss. Losses for assets held for over a year generate long-term losses.

Related: 11 Ways to Avoid Taxes on Social Security Benefits

“Netting” Rules

You must follow a certain sequence when offsetting capital gains with capital losses. This is known as “netting” capital gains and losses.

The order is as follows:

1. First, you must offset short-term gains with short-term losses.

2. Second, long-term capital gains are offset with long-term capital losses.

3. Last, if there are any net losses of either variety, they can then be used to offset gains remaining of the opposite type (if there are any).

Like Young and the Invested’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Example

Charlie realized the following gains and losses during the year:

— $400 short-term capital gain

— $700 long-term capital gain

— $500 short-term capital loss

— $300 long-term capital loss

Charlie first offsets the $400 short-term gain with the $500 short-term loss, resulting in a $100 net short-term loss. He then offsets the $700 long-term gain with the $300 long-term loss, resulting in a $400 net long-term gain. Finally, Charlie offsets the $400 net long-term gain with the $100 net short-term loss, resulting in a $300 net long-term taxable capital gain.

Deducting Net Capital Losses From Ordinary Income

If you have a net capital loss after netting capital gains and losses, you can deduct up to $3,000 of it from your “ordinary” taxable income, such as wages, interest, IRA or 401(k) account distributions, and the like (up to $1,500 for a married person filing a separate return). Anything over the $3,000 (or $1,500) limit is carried forward and applied against gains or deducted from ordinary income in future years until it’s all used.

Example

Greyson had $50,000 of ordinary taxable income and realized the following gains and losses during the year:

— $5,000 short-term gain

— $3,000 long-term gain

— $4,000 short-term loss

— $9,000 long-term loss

After netting all capital gains and losses, Greyson has a $5,000 net long-term capital loss. He can deduct $3,000 of the net loss from his $50,000 of taxable ordinary income, resulting in $47,000 of taxable ordinary income. The remaining $2,000 of net loss is deducted from taxable ordinary income for the next tax year.

Related: Best Vanguard Retirement Funds for a 401(k) Plan

Wash Sale Rule

Perhaps a light bulb went off over your head after reading about offsets and deductions for capital losses: Why not sell stock that has lost value to generate a loss, then turn around and buy the same stock back the next day? You’ll have the loss to counter any capital gains, but still hold the same investment property.

Unfortunately, there’s a rule that prevents you from taking advantage of “manufactured” investment losses of this sort—it’s called the wash sale rule.

Basically, under the wash sale rule, you can’t offset capital gains or claim a deduction against ordinary income with losses from the sale of stock or securities if you buy or otherwise acquire the same or substantially identical stock or securities within 30 days before or after the sale. The rule also applies if you sell stock and your spouse buys substantially identical stock within the prohibited time period.

Related: Tax-Loss Harvesting: How Investors Can Cut Their Tax Bill

There’s a silver lining if you’re caught by the wash sale rule, though. The disallowed loss will be added to the basis of your newly acquired stock (remember, a higher basis is good when you eventually sell that stock). The holding period for the stock you sold transfers to the newly acquired stock, too. As a result, you might be able to sell the new stock in less than one year but still have any gain taxed at a long-term capital gains tax rate.

Young and the Invested Tip: The wash sale rule doesn’t apply to cryptocurrency, since it isn’t considered stock or a security. So, you can sell cryptocurrency one day for a loss and buy it back instantly without incurring any penalty.

Like Young and the Invested’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Capital Gains Tax Rates

If you end up with a net capital gain after netting gains and losses, the tax rate that applies depends on whether the gain is long-term or short-term capital gain. In most cases, the tax rate on your net capital gains will be lower for long-term gains, which creates an incentive to hold on to investments and other assets for more than a year if possible.

There are also some special capital gains tax rates that apply in certain situations.

Related: What’s Your Standard Deduction?

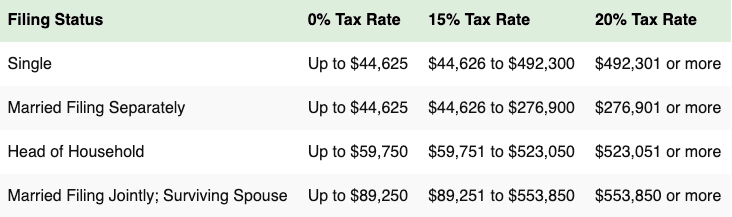

2023 Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Rates

Long-term capital gains are taxed at either a 0%, 15%, or 20% rate, depending on your taxable income. For 2023 tax returns, which were due on April 15, 2024, for most people, taxable income is found on Line 15 of Form 1040.

For the 2023 tax year, the long-term capital gains tax rates (based on taxable income) are in the picture above.

Related: 2024 Tax Calendar (Tax Deadlines for the Entire Year)

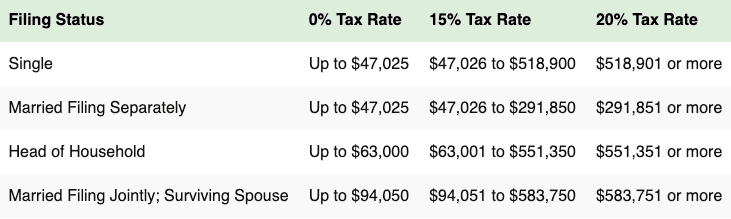

2024 Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Rates

The dollar amounts in the long-term capital gains tax rate brackets are adjusted each year to account for inflation.

If you’re looking ahead to your tax return for the 2024 tax year (i.e., the tax return you’ll file in 2025), the long-term capital gains tax rates are in the image above.

Related: IRS Erases $1 Billion In Back Tax Penalties

Short-Term Capital Gains Tax Rates

Your short-term capital gains rate is the same as your “ordinary” income tax rate. These tax rates range from 10% to 37%, depending on which federal income tax bracket applies to you. Like each tax bracket above for long-term capital gains taxes, the federal tax brackets for ordinary income are based on your filing status and taxable income.

You can find both the 2024 and 2025 federal tax brackets (and, therefore, the short-term capital gains tax rates for those years) at Federal Tax Brackets and Rates.

Special Capital Gains Tax Rates

The following special capital gains tax rates apply:

— 28% for the taxable portion of a gain from selling qualified small business stock (a.k.a., “Section 1202 stock”)

— 28% for collectibles (e.g., art, coins, stamps, historic artifacts, etc.)

— 25% for unrecaptured gain from selling certain real estate (“Section 1250 property”) subject to depreciation

Each special capital gains rate is a maximum rate. As a result, your ordinary tax rate might still apply to short-term capital gains on the sale of qualified small business stock, collectibles, or Section 1250 property if it’s higher than the special maximum capital gains tax rate.

Related: 11 Education Tax Credits and Deductions

Net Investment Income Tax

In addition to paying capital gains taxes on investment profits, you might also have to pay what’s called the net investment income tax. This 3.8% surtax is imposed on your “net investment income” if your modified adjusted gross income exceeds a certain amount.

Among other things, your net investment income generally includes interest, dividend income, capital gains, rental and royalty income, and non-qualified annuities. It doesn’t include wages, unemployment compensation, Social Security benefits, alimony, and most self-employment income. Net investment income also doesn’t include any gain on the sale of a personal residence that’s excluded from gross income for regular income tax purposes.

The income thresholds, which are based on your filing status, are in the image above.

For purposes of the net investment income tax, modified adjusted gross income means the adjusted gross income reported on your federal income tax return (Line 11 on your 2023 return), plus any excluded foreign earned income.

Use Form 8960 to calculate the 3.8% tax.

Related: Best Fidelity Retirement Funds for a 401(k) Plan

Reporting Capital Gains and Losses on Your Tax Return

If you sell a capital asset, you might have to file additional forms with your federal tax return.

Schedule D is used to calculate capital gains and losses, which are then recorded on Line 7 of Form 1040. Among other things, you can also report a capital loss carried forward from the previous year on Schedule D. You don’t have to file Schedule D if you:

— Aren’t deferring any capital gain by investing in a qualified opportunity fund

— Don’t have capital losses, and your only capital gains are capital gain distributions from a regulated investment company or real estate investment trust

— Don’t have unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, Section 1202 gain, or gain from the sale of collectibles

Form 8949 is used to report sales and exchanges of capital assets, and allows you to reconcile amounts reported to you (and the IRS) on other forms with the amounts reported on your return. The subtotals from Form 8949 are used to complete Schedule D. If you aren’t required to file Schedule D, then you’re not required to file Form 8949, either. Check the instructions to Form 1040 (Line 7) for other situations where you aren’t required to file Form 8949.

If you sold or exchanged depreciable assets used in a trade or business, you might have to file Form 4797 as well.

Digital Assets

The IRS is very interested in transactions involving cryptocurrency and other digital assets like NFTs, since capital gains from these transactions often go unreported. As a result, there’s a question near the top of Form 1040 asking if you received, sold, exchanged, or otherwise disposed of a digital asset (or a financial interest in a digital asset) at any time during the tax year.

Make sure you check the applicable box (Yes or No) for that question … and remember that if you disposed of any digital asset that you held as a capital asset, report the gain or loss on Form 8949 and Schedule D.

Related: Best Schwab Retirement Funds for a 401(k) Plan

State Capital Gains Taxes

Unless you live in a state that doesn’t impose an income tax, state capital gains taxes apply in most cases. Generally, the capital gains included in your state taxable income are treated and taxed at the same rate as other income, regardless of whether they’re long-term capital gains or short-term capital gains.

For more information on state taxes on capital gains, check with the state tax agency where you live.

Young and the Invested Tip: Although it doesn’t impose an income tax, Washington State levies a 7% tax on long-term capital gains.

Related: States That Tax Social Security Benefits

How to Reduce or Avoid Capital Gains Taxes

As with any other type of tax, you want to lower or even avoid federal capital gains taxes if you can. There are several ways to whittle down your capital gains tax and cut your overall tax bill in the process. Some methods take advance planning, while others can be implemented relatively quickly. And, of course, some might not be practical or even feasible for you.

To get you thinking about ways to slash your capital gains taxes, here are some quick-hit capital gains tax strategies that might be right for you:

1. Hold assets for more than one year before selling for a profit.

With a long-term gain, you’ll qualify for a lower capital gains tax rate. These long-term capital gains rates are generally more advantageous than the applicable short-term capital gains rate (ordinary income tax rates).

2. Sell investments or other assets that have declined in value to generate capital losses.

When you sell investments or other assets that have declined in value, they generate capital losses that you can then use to offset capital gains. This approach is commonly referred to as “tax loss harvesting.” Be mindful of one provision that can affect your timing of taking advantage of this strategy called the “wash sale rule,” which prohibits you from deducting capital losses from the sale of an asset if you buy it (or a very similar asset) back within a 30-day period before or after the sale.

3. Place assets that are likely to increase significantly in value in tax-advantaged retirement accounts

To minimize how much you pay in capital gains, you can place assets likely to appreciate in value inside a tax-advantaged retirement account, such as a traditional IRA. If you sell assets in these accounts, you don’t have to pay capital gains taxes. However, withdrawals from these accounts will be taxed at ordinary income tax rates regardless of how long you held the asset.

4. Donate the appreciated property to charity

Consider donating appreciated property to charity to receive a tax deduction for the property’s FMV. Under certain circumstances, the FMV is reduced by any long-term capital gain you would have realized had you sold the property. Your charitable tax deductions might also be limited to up to 50% of your adjusted gross income.

5. Use a Section 1031 exchange

If you’re selling investment real estate, defer capital gains taxes with a Section 1031 like-kind exchange. If you use the profits from the sale to purchase real estate of the same nature or character, then any gain or loss generally won’t be recognized until you sell or otherwise dispose of the new property.

6. Stay put in your primary residence for a little while longer

Delay selling your home if you haven’t lived there very long. If you expect to owe capital gains taxes on the sale, you definitely don’t want to leave the $250,000 exclusion ($500,000 if married filing jointly) on the table. If you currently don’t meet the ownership or residency requirements, consider postponing the sale until you do.

7. Consider Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds

You can defer or eliminate capital gains taxes if you invest profits from the sale of property in a Qualified Opportunity Fund, which then invests in economically distressed communities. Your capital gains tax liability can be deferred until 2027. In addition, if you hold your investment in a QOF for 10 years, your basis is increased to 100% of the investment’s FMV (other basis increases are available if you hold the investment for five or seven years).

Check with your tax advisor to see if any of these strategies can provide tax advantages for you and reduce your overall tax burden.

Like Young and the Invested’s content? Be sure to follow us.