Landlords have been on the receiving end of a heightened financial beating for the past few years.

A variety of cost pressures more directly impacted by COVID, such as commodity and labor-cost inflation, have received ample media attention. But less discussed, largely because of its dry nature, is landlord insurance—a cost that’s equally if not more impactful, and that is continuing to squeeze higher even as other COVID-related price spikes have flattened.

How Much Have Insurance Premiums Risen?

After financing, insurance is generally a landlord’s largest expense line item. And that line item has been rapidly climbing uphill.

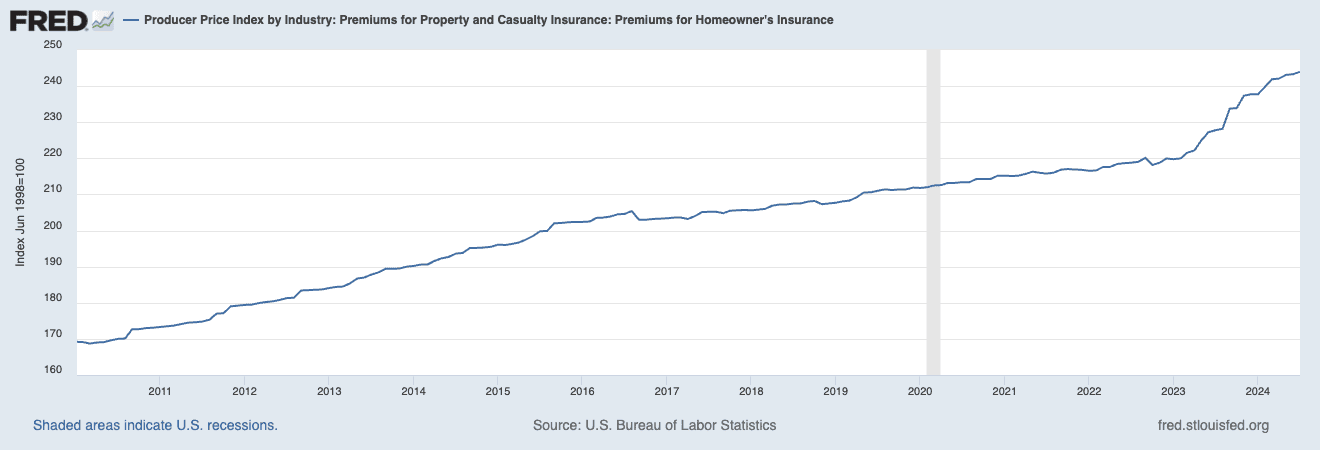

Federal Reserve data shows that the producer price index (PPI) for homeowner’s insurance premiums has risen by nearly 30 points since the start of 2020—that’s an annualized growth rate of about 3.2%. That’s considerably quicker than the 2.3% annualized rate across the decade prior.

The situation looks much worse in practical terms: Growth in average homeowners’ insurance premiums (which lump in 1- to 4-unit single-family residential rentals) varies depending on the data source, but broadly speaking, they have risen by 25% to 45% over the past four-plus years. For instance, in its State of Home Insurance in 2024 report, LendingTree found that “home insurance rates in the U.S. are up 37.8% cumulatively since 2019.”

“Rates are high for everyone, not just landlords,” says Laura Olson, Chief Insurance Officer of Obie, an insurance-tech company that serves real estate investors in 49 states. However, given the nature of their business, landlords have to eat higher rates than your average homeowner. “Historically, tenants don’t take care of a property as well as a homeowner. So there’s usually a 20% to 25% surcharge, all other things being equal, if a house is tenant-occupied [compared to owner-occupied.]”

Of course, just how painful your insurance-premium hikes have been will vary depending on where you live.

“Depending on where you’re at in the country, you could easily have seen 10%, 15%, 20%, 25% increases annually,” says Aaron Letzeiser, Obie Co-Founder and COO. “Unfortunately, if you’re in areas that are popular to invest in—Sun Belt states, and other emerging rental housing markets, where the challenge is a lot of hurricane and weather risk—in those markets, you could have seen 30%, 35%, even 50% increases.

“If you owned large multifamily buildings, you might have seen rates double.”

What Has Been Pushing Rental Insurance Rates Higher?

Like most things, the surge in homeowners insurance premiums was exacerbated by COVID, to be sure. But rising insurance costs are hardly a new phenomenon—available PPI data only goes back to 1998, but that data shows premiums have climbed virtually unimpeded for a quarter of a century.

That’s why it’s important to understand the myriad sources of upward pressure on landlord insurance costs—geography, weather, regulation, existing insurers, and inflation among them.

Because while a few of them might ease now that the COVID lockdowns and supply-chain disruptions are largely in the rear-view, others could remain persistent … and a few could even pick up speed as time marches on.

Geography

Many sources of insurance-premium inflation are intertwined in some way, but a pair of the most dominant drivers—weather and regulation—are largely dictated by where you own property.

Weather

Catastrophic and extreme weather events such as hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes have been recorded for millennia. There’s ample history of where these events occur, and insurers’ rates reflect that.

As you’d guess, the places with the greatest frequency of catastrophic events (and the highest costs to recover from them) are the places where insurance is costliest and hardest to procure: California, Texas, Louisiana, Florida. Other coastal states, such as the Carolinas, can be problematic but aren’t as difficult given that a greater proportion of their states are farther inland. Insurance is far less problematic as you travel further inland to areas such as the Midwest and Rocky Mountain states.

What’s pressuring insurers to raise rates is the fact that the cost of the damage these events cause (and thus the proceeds that need to be paid out) is rising … as is their frequency. Consider these statistics from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI):

- Between 1980 and 2023, the U.S. averaged 8.5 events per year that caused more than $1 billion or more in damage (adjusted for inflation).

- Over the past five years, the U.S. averaged 20.4 billion-dollar events annually.

- In 2020, the U.S. experienced a record 22 billion-dollar events, at a cost of about $95 billion.

- In 2023, the U.S. broke that record with 28 billion-dollar events, albeit at a slightly lower cost of $92.9 billion.

- As of Aug. 8, 2024, the U.S. was at 19 billion-dollar events for the year.

But another factor putting the squeeze on insurers is more unpredictable weather.

Consider the “Great Texas Freeze” of 2021, which claimed more than 200 lives. In Texas, many homes don’t have basements and sit right on the soil—the freeze disrupted foundations, and also froze pipes, which burst, causing flooding and water damage. Early cost estimates started at around $80 billion; by 2022, the Texas section of the American Society of Civil Engineers pegged the economic impact at closer to $300 billion. More than 100 people perished in 2023’s Maui, Hawai’i wildfires, which caused more than $5.5 billion in damages. Colorado has suffered a pair of billion-dollar wildfire events over the past five years. Average annual statewide temperatures have risen by 2.3°F between 1980 and 2022, above the global mean; an expected continuance in rising temps could put Colorado at even greater risk.

“There’s a higher frequency and severity of these weather events than in the past … and recently, you’ve had more unpredictability,” Letzeiser says. “That’s contributing to a higher incidence of loss, and insurers that are taking on more loss must raise rates to offset.”

One last factor outside the weather itself is the increasing population density in places more prone to catastrophes.

“Even in states like Arizona, the Sun Belt, coastal areas, the number of communities and properties that we as a society have built in these majorly exposed areas has increased,” Olson says. “Because the demand for housing has become so great, we’re building in places we’ve never built before. And every time we rebuild, we rebuild in the same town.”

The pandemic played a small hand in at least temporarily accelerating this. Specifically, as more and more people could work from home during the worst of COVID, they moved … often to states with good everyday weather—Florida, Texas, California—that also happen to routinely suffer catastrophic weather events.

Major carriers have specifically cited climate risk in requesting rate increases. State Farm was allowed to increase homeowners’ insurance rates by 20% in March 2024; they’re currently seeking another 30% rate hike for homeowners’ and a 36% increase for condominium owners. Allstate is currently seeking a 34.1% increase to homeowners’ rates in California; earlier this year, one of its subsidiaries (Castle Key Indemnity) requested a 53.5% hike that is still under review.

Regulation

Where you live also has a massive say in how much insurers can raise rates, how often, and how quickly requests to do so are fielded. In some cases, those regulations protect consumers from sharp and/or usurious increases in their premiums; but in other cases, they make it so difficult to operate that insurers simply exit the state altogether or stay but risk going under.

In California, for instance, if an insurer proposes a rate increase of more than 7%, a consumer intervenor can request a mandatory public rate application hearing, which can slow and even stop a request.

“For decades, then, some companies will only file for 6.9% or below,” Olson says. “So if in one year, my rate need is 10%, or 20%, and I can only file for 6.9% in a year, and this happens over many years, I’m going to be filing in perpetuity. That’s why a lot of insurers pulled out.” (Editor’s note: Obie has remained in California.)

Another issue—one that was made much worse by COVID—is backlog.

“The way insurance works is, if you’re in the admitted companies (they’re licensed in the states in which they operate)—name brands like Allstate and Nationwide—they have to submit filings to each state that show their loss costs, experience analysis, and justify if they want to increase rates,” Olson says. “Some states are ‘use and file’—you can start applying those rates to the market the day you file. But most states require prior approval. And during COVID, departments of insurance shut down.”

Even now, some states are still working to get back to their pre-COVID pace. California makes for a good example yet again: The state’s insurance department requires decisions on rate filings within either 60 days if no hearing is requested, or 180 days if there is a hearing. Michael Soller, spokesperson for the California Insurance Department, said in February 2024 that the average time for homeowners’ insurance filings was 196 days.

Olson adds that in states where there are several “stage gates” and a longer approval process, some might see their landlord insurance rates remain stagnant while others’ are rising, then suddenly experience a massive premium hike themselves.

“So, not only do you have to have enough data, and not only do insurance companies have to wait for trends to show up, but even when they had the data, they were filing then waiting months or years to get an answer,” Olson says. “There’s a lot of latent demand in rates that got bottled up in the past three years.”

Exiting insurers

The exit of an insurance carrier is a significant factor in the overall supply and demand in the state’s market.

If a carrier leaves the market, the remaining carriers might not be able to assume the additional risks … and if they do, it likely will come at an increased cost thanks to aggregation and reinsurance issues. Landlords have already seen this in play in California and Florida, where many carriers have left, and the remaining major carriers have requested significant rate increases.

“Carriers exiting markets also applies pressure to the state’s carrier of last resort (FAIR plans, Citizens Property Insurance Corp.), as they will end up writing this business, which could impact taxpayers,” Olson says.

Conversely, the more insurers you can bring back into a market, the more benefit for consumers. For instance, in the face of growing competition, a major carrier might cut prices to drive market share and bet against a bad hurricane season or wildfire season. The bet might not pan out for the insurer, but it’s likely the consumer will end up benefiting.

Inflation

Landlords who built or repaired homes during COVID felt the direct brunt of commodity and labor inflation pretty much immediately.

But in the ensuing years, they’ve felt the ripple effects—through higher rates from insurers.

Some insurance carriers will give you a guaranteed replacement cost, which means in the event of a total loss, the insurer will cover all costs to rebuild the home. That guarantee stands even if that cost is greater than your policy limit. So an insurer might have run models in, say, 2018 or 2019 that provided a certain cost for rebuilding a home. But if a policyholder had a total-loss event in 2020 or later, that replacement cost might have been significantly more than what they modeled, which would eat into the insurer’s reserves.

“We have an investor that bought an apartment portfolio in Florida—2,000 small apartments. And he hadn’t changed his replacement cost,” Letzeiser says. “The carrier and these investors agreed effectively through their contracts that they were going to replace at $65 per square foot. In 2020, you couldn’t replace even old construction at that price.”

Those higher costs might very well be a new normal. U.S. construction costs have soared by 25% to 40% since 2020, according to Toronto-based Altus Group, a provider of asset and fund intelligence for commercial real estate. While prices are stabilizing, they’re doing so by returning to a historical growth rate in the low- to mid-single digits.

“If this is the new normal,” Olson says, “none of the insurance companies are ready to absorb this.”

Insurer Viability

Here’s an oversimplified view of how an insurance company makes money. An insurer takes in premiums priced to allow a statistically probable chance of earning a profit, invests that money (property and casualty insurers commonly invest in bonds), pays out proceeds when needed, and hopes to make enough income off the investment float and policy pricing to stay in business.

A good framework to remember, Olson says, is that in property insurance, loss ratios for non-catastrophic events are 40¢ to 50¢ out of every dollar. That’s 40¢ to 50¢ of every premium dollar going toward paying claims. “When you have weather events, ‘cat’ (catastrophic) events, that loss ratio can spike to 75¢, 80¢, even a dollar of every dollar,” she adds.

And that’s before general and administrative expenses, commissions, and so on.

Between 2020 and 2022, as interest rates hit near-zero and inflation took off, some insurers were spending closer to $1.25 for every $1 of premium they took in, and bonds were yielding next to nothing so insurers couldn’t make money on the float anymore. Both pressures have eased since mid-2022, but with the Federal Reserve likely to begin a rate-cutting cycle before the end of the year, insurers will yet again have to review their investment strategies.

Combine that with insurers starting to suffer weather losses in places they never had before, and a lot of farm bureaus and regional insurers have run out of capital and gone out of business.

What Can Landlords Do?

Well, you sure can’t prevent a hurricane or a tornado. And as long as the data dictates it, you can expect general homeowners’ premium growth to continue trudging forward.

But there are a few actions you can take to secure a lower rate, whether that’s now or down the road. That includes installing smart devices, educating your tenants, utilizing a property manager, routinely performing maintenance, and more.

Install Smart Devices

“Internet of Things” (IoT) and other connected devices might provide premium relief, but even if they don’t, you’ll have some peace of mind.

Devices such as smart CO2, smoke, fire, and burglar alarms are better known, but there are others. For instance, there are water leak detectors you can put under sinks, pipes, and water heaters to notify you of leaks, enabling you to, say, fix a burst pipe before it can do too much damage. There are even puck-sized fire extinguishers that go underneath your hood vent or above-oven microwave and release fire suppressants if they get too hot.

In many cases, these devices aren’t all that expensive, either. For example, Stovetop Firestops cost less than $30 each; a Ring Alarm Flood and Freeze Sensor is about $35.*

Olson notes that some of these devices haven’t hit the mainstream yet “because the last mile of installation is a nightmare.” The exception? New homes, where you can put them in on the build.

Whether they’ll affect your rates in the short-term is an open question, but they should have an eventual impact one way or another.

“Insurance runs on a terrible phrase, which is ‘10 years of loss history and 10 years of policy history to make a change.’ Insurers take a long time before making a decision because it’s a risk-averse industry. So a lot of carriers haven’t implemented a discount—but some carriers have,” Letzeiser says.

However, even if your carrier doesn’t provide a specific discount for any of these devices, “you’re building your own discount,” he says. After all: If you don’t have to file a claim, your rates won’t go up as a result of a claim, or your carrier might not drop you as a result of a claim.

Utilize a Property Manager (Or Keep Up With Maintenance Yourself)

Olson says a property manager is “an inherent risk mitigation/loss mitigation tool.”

Property managers offer a wealth of upsides that insurers favor. When a property manager is in place, it’s likelier that more preventative maintenance is being performed (and thus they’re preventing losses rather than fixing them after the fact). They tend to do tenant screening. They tend to have less liability risk than landlord-managers.

Obie doesn’t yet provide discounts for property managers, Olson says, but they’re collecting data in hopes of eventually doing so.

“Our hypothesis is good partner (i.e., property manager) equals a good insurance risk,” she says. “We have maintenance data, tenant info, occupancy rates, rent rolls, and more about the property. We need enough insurance data to have credibility that the data is giving us a signal for discounts or surcharges.”

If you don’t have a property manager, be sure to keep up on maintenance yourself. You can use tools like Latchel, that are integrated into real estate software systems like Baselane, to help streamline the workflow. (Latchel can manage work by licensed professionals, and even send you proof of work.) Also, don’t cheap out on projects—you’ll pay for it later.

Educate Your Tenants

Letzeiser says that two of the biggest causes of loss under your control are tenant-caused fire and water damage. And you can significantly cut back on those losses by providing a few educational tips upon move-in, including telling tenants:

- Where the fire extinguisher is

- How to use the fire extinguisher

- Which circumstances require use of the fire extinguisher (Oven fire? Keep the oven closed and stand by with the extinguisher. Stove fire? It’s likely a grease fire, and water won’t put that out. Use the extinguisher.)

- Where the water main shutoff is

- Where the shutoff knobs for toilets and sinks are

Tenants should also be encouraged to perform preventative maintenance such as regular cleaning and seasonal checklists.

Continuously Update the Property

You should always keep a maintenance checklist and shouldn’t necessarily sink a bunch of money into renovations just to get a better insurance rate, but if you were going to do those things to protect your assets or raise the rent you can charge, it doesn’t hurt. Updated HVAC units can help with rates. Insurers probably don’t want to see a 40-year-old roof.

A specific thing to look for, Letzeiser says, is circuit breakers. Make sure you don’t have Federal Pacific Electric (PFE) or [Zinsco] circuit breakers. Most are not to code, but some buildings still have these things. There’s a preponderance of evidence that if you have an electrical fire, it’s due to this, he says, adding that these two brands are the most often put into applications for insurance. So landlords should check out fuses right away.

Olson suggests that, earlier in the deal flow, to pay attention to where you’re buying and what you’re buying—the types of materials, the size, the age, the roof type, the plumbing, the HVAC, whole-house systems. Collectively, they can heavily impact pricing.

On new builds in catastrophe-prone areas, look into innovative build materials. For instance, in places that experience wildfires, you’re finding communities built with fire-resistant materials. In Florida and other coastal areas, you’re seeing hurricane-resistant roofs, shutters on windows, and builders are even building higher off the ground.

Check Your Maps

If you’re buying or building in low-lying coastal areas, you probably know to check out federal flood insurance maps. However, floods don’t just occur in areas near bodies of water—they can also occur during periods of heavy rain in areas with poor drainage infrastructure.

Federally drawn maps show the likelihood for flooding, and insurance companies rely on these to determine risk when pricing flood insurance policies. Before buying or building a property, you’ll want to consult these maps to understand the level of risk flooding presents for this area.

One Thing You Shouldn’t Do

The biggest financial gamble you can make, by a country mile, is going under-insured.

“If you’re going to pay for insurance, make sure you’re properly covering the property. I’ve seen instances where a person is so undercovered that there’s not enough to replace the property,” Letzeiser says. “The lender says, ‘Cut me my check for this property you own,’ and you, as the homeowner, depending on your loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, might just get a check for 30% of the value, and then all you have left is a burned-out building and a piece of land.

“So if you’re going to pay for insurance, it might only cost you another $50 to $100 [monthly] to get enough coverage to fully replace it.”

* Not an explicit recommendation of any specific product. Products shown are provided only as examples.